The fast train from Tashkent to Samarkand takes just over two hours. A comfortable journey, with staff welcoming you at the door of every carriage (and checking your ticket), very much like an airline crew would. The trains get booked up very quickly, even in winter, and I dread to think what it might be like in high tourist season. Tickets are wonderfully cheap – long may it last – about £13 one way to Samarkand, then £9.60 to carry on to Bukhara. I shall also be taking a sleeper (at an ungodly 03:50, a night train that starts in the east of the country) to Khiva, a 6,5 hour trip, for £13.

The Bolshevik revolution and subsequent Soviet rule were not a blessing. However, the railways built across the USSR, linking all 16 (former Soviet) republics, made an immense change in the cultural and economic landscape of Central Asia. The rail tracks are still in place, but a number of them are not in use and often are not maintained. Local issues, long standing fights over territory, arbitrary rules, political unwillingness, make land journeys much longer as one needs to nip back into other countries. You have to go from Turkey to Georgia to get to Armenia (tantalising, seeing the border you cannot cross), then again to Georgia to get to Azerbaijan. The next bit of toggling will be going from Tajikistan to Kyrgyzstan, via Uzbekistan.

Samarkand. Even the sound of the name has an exotic, magical quality to me. My little B&B was hugging the walls of Gur-Amir Mausoleum, a graceful building with a usual tall arched entrance, a courtyard, and the mausoleum itself where the jade tombstone of Amir Timur lies among other family tombstones. It was good to see plov (Uzbekistan rice, meat and vegetable dish – like a pilau) being prepared for lunch on one side of the courtyard of the Gur-Amir mausoleum; on the other side is the giant block of stone, thought to have been a pedestal for Amir Timur’s throne, and an immense font that would have been filled with pomegranate juice for his soldiers to drink.

Amir Timur desired to be buried in his birthplace, Shakhrabaz, but Samarkand had been his royal seat, and so others decided he would stay there. The guides tell a nice story about the way he is depicted in different places – in Shakhrabaz, he is standing – that’s where he rose; in Tashkent he is on a horse, for his victories, and in Samarkand, he sits, as this was his capital.

The Registan, with famously gorgeous buildings on its three side, the gently leaning minarets, the blue of the tiles and the intricacy of the calligraphy in stone, the geometric designs weaving seamlessly throughout, does not disappoint. The pale marble square makes the colours stand out even more. (Though there is a little problem, especially on the marble viewing platform when it snows/ is wet – it becomes very slippery and even the sweepers with their besom brooms shuffle carefully across this shiny skating rink.)

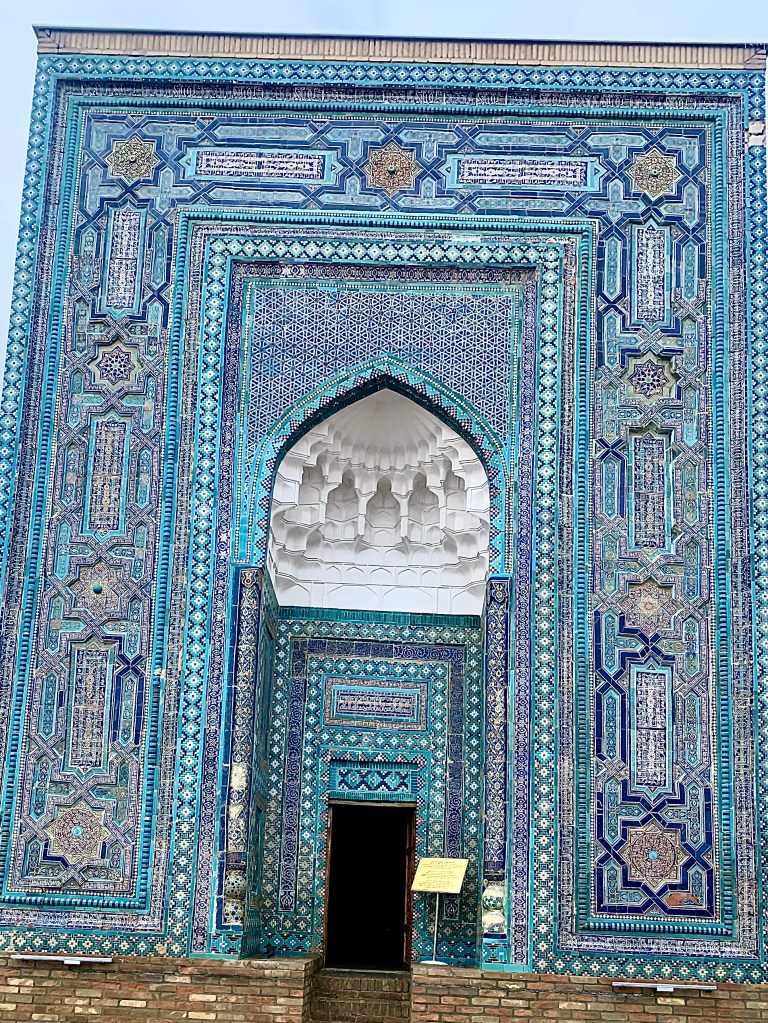

The blue tiles of Shah-i-Zinda are dazzling, the arabesques and designs whirl with colour and beauty. It struck me that the majority of the places we come to see are tombs, necropolises, mausoleums, cities of the dead.

There are a number of madrasahs, mosques and museums, that are currently being renovated – some will be ready for the season which is due to start in March, but not all. I found it interesting that a museum such as Afrasiab, “the most important museum in Samarkand” (it is a long walk to it from the Bibi-Khanim Mausoleum – about 4 km) was very much open and charging for entry, despite the fact that there were fewer than half exhibits available, workmen drilling and definitely no video explaining the frescoes (needed, as the originals are faint and missing some key parts). The archeological site of the fort (one of the largest in the world) was so muddy and waterlogged, I didn’t need to be told there was little point in going there.

Ulug Beg was one of Amur Timur’s grandsons, and well favoured (he was given Bukhara and Samarkand, among other bits, as a gift). He is known as the Astronomer King and his observatory, built in the 1420s, provided measurements so accurate that some have not been bettered until the computer age. The one part that has survived the destruction wreaked by fanatics (no change there) in 1449 is a part of the meridian arc. The radius of the sextant had been just over 40m, and the solution to the problem of having a building that could accommodate it without collapsing on itself was to sink the arc into the ground. (The Lonely Planet and Wikipedia provided the information.) One can still see the notches used for the measurements on the metal and it must have been a sight to behold when the sextant and the astrolabe were in place.

I can’t help but mention one more mausoleum – that of Daniel, of the lions’ den fame. Samarkand is one of 6 places that has the tomb of Daniel. It is a place of pilgrimage and there is a spring of water below it that is thought by many to be sacred. The legend has it that Daniel’s severed leg (could not find any reference to how it got severed) keeps growing inside his marble tomb . The tomb is currently 18m long and it is said that when the leg reaches it, “the world will surely end”.