(The process to enter Turkmenistan started well before I left the UK – one cannot visit the country without a Letter of Invitation (LOI), usually provided by a travel agency which then also organises the visit in full. The letter is valid for a month and the transit visa gives you 6 days within that month. The trip is not cheap, especially if it is for one person, as in my case. Owadan Travel is a government approved agency and Saray, the lady with whom I dealt online, has kept me informed throughout. I was initially taken aback when I was told that they would only accept cash payment (in crisp $ notes) . Carrying $2500 – $3000 in cash around Central Asia for months was not an option. On arrival in Ashgabat, my guide took me to the Central Bank to get the cash. I visited their offices and met the owner and members of staff, was shown their little ethnographic museum and given a small present.)

There are no direct flights from Baku, Azerbaijan, to Ashgabat and the Caspian sea port at Turkmenbashi is closed to tourists. Thus, a change of plan and “doing” Uzbekistan first, so I could use the land border crossings. The crossing at Shavat (Uzbekistan side, not far from Khiva) wasn’t very busy at 09:30 am (it is open from 09:00 – 17:00). Just a dozen of us, with me the only non-local – and once the passport was stamped and the luggage put through the scanner, I could walk towards the no man’s land. Beyond the Uzbekistan border fence there was an old commuter type bus, battered, mauled and scarred, likely from the Soviet times, but I was truly grateful that I wouldn’t have to walk the mile or so to the Turkmenistan border fence with my luggage on my back.

The very young Turkmen soldier (military service is obligatory for men at 18; they can defer it if they go to university but need to do it after) took my passport and the LOI and passed it on to someone else… It took about an hour, some 8 people, including my guide (who was called by one of the 8), a doctor (to do a $33 PCR test), various small window counters, old technology, various bits of paperwork, the payment… and I could finally put my luggage on the scanner. Having read about people’s bags being searched to the last pocket and seam, it was a pleasant surprise when the officer said “welcome to Turkmenistan” and asked, smiling, if I smoked, had any codeine based drugs or heroin.

Mekan, the Owadan Travel guide, is a 25 year old English language and literature graduate (studied in Turkey) who can guide in English, Russian and Turkish. Guwanch, the driver of the gleaming white Toyota Hilux, looked a little apprehensive when I usurped the front seat – until he realised I spoke Russian – he then visibly relaxed. He is a good and conscientious driver (seatbelt on at all times!) and we got on very well. (I called him “my hero”, after a particularly scary road bit was negotiated with panache, and he remained “Мой герой” (Russian for ‘my hero’) throughout. I was presented with a lovely box of chocolates by him – he did say this was the first time he ever bought anything for a tourist.

The roads are abysmal. Rutted, potholed, scraped, ploughed, furrowed, scarred, disappeared. The dual carriageway (not always dual) was used on both sides in both directions as each driver tried to find the least damaged bit to drive over. We drove on the right and on the left, overtook on any side, went off road when that was the least awful part. Guwanch manoeuvred the 4-wheel drive Toyota Hilux with (new) heavy duty winter tyres with skill and panache – he had a schedule to keep (to get me to all the places on the programme – we did 310 km on the first day). That day, the wind was up, the sand carried across the road in gusts as blinding as a sudden fog. We saw a tree brought down by the wind that crashed onto the electric wires and broke them – it looked like the ground was burning and Mekan called the provincial fire brigade to tell them about it.

Turkmenistan is 80% desert; its riches, the natural gas, the minerals, ore, are all underground. The soil is salty. I thought at first it was hoarfrost on the ground (also in Uzbekistan) – it is salt. They do grow excellent fruit and vegetables in the areas near the water – melons and cantaloupes are especially highly rated.

We headed to the first historic place on our sightseeing tour - Konyeurgench. It has a long history, starting in the 5 ct BC, but its heyday was between 11-14 ct when it was the capital of the Kwarezm empire and an important, rich, well developed town on the Silk Road. (Of course, it got raided and sacked and rebuilt several times.) It is now a UNESCO site.

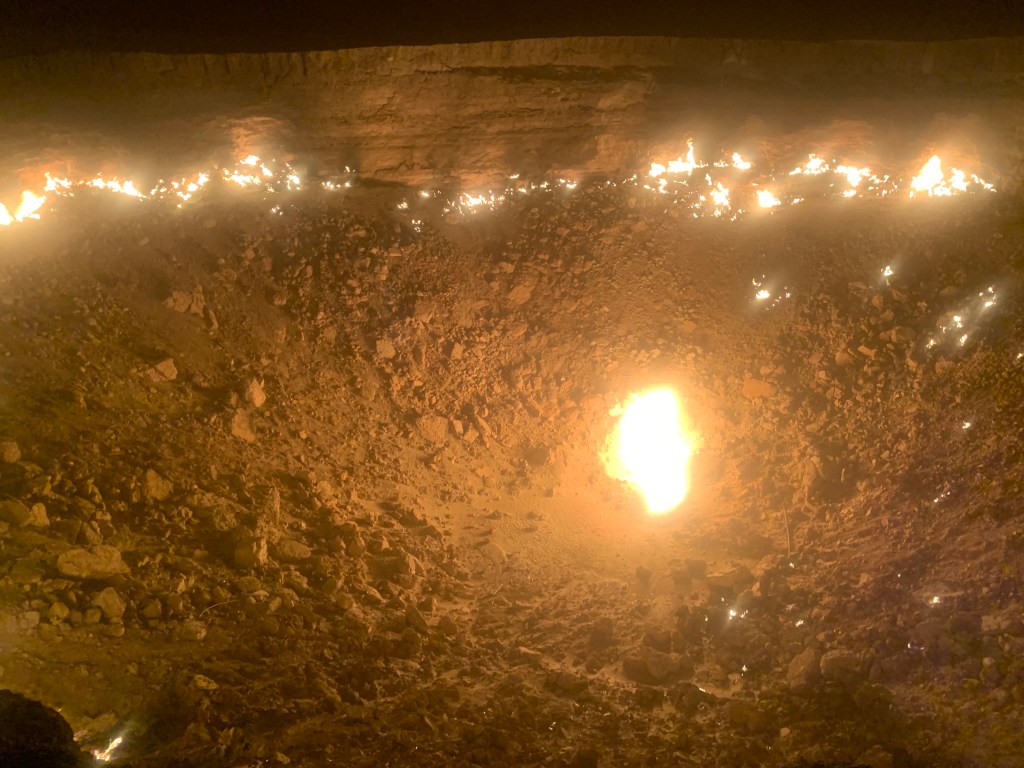

Then a long drive to Darwaza, in the middle of the Karakum desert, where The Gates of Hell gas crater has been burning since the 1970’s when the Soviet experts were prospecting for natural resources (Kara-kum means ‘black sand’, as there is a lot of shale underneath). I was told there had been a lot of heavy equipment in the area at the time and a spark may have caused an explosion that created the crater – there are metal bits and pipes visible at the bottom. The natural gas has been burning since. (It made me smile, thinking of the Azerbaijan’s “Fire Mountain”, which is but a smidgeon compared to the hundreds of clean, smokeless flames around the giant crater.

Owadan travel built and owns the yurts here and this is where I slept. This being February, I was, yet again, the only visitor. But I was well looked after, and there was a fire in the little stove in the yurt. (The loo, though, could not be put closer – at 50m, it is a trek.)

Ashgabat is officially “the whitest city in the world”. The buildings cannot be painted anything but white; the only cars allowed inside the city limits must be white, silver or gold; the street lights (and there are, for once, plenty) are all on white or silver posts. The cars must be clean – else they will get stopped by the traffic police and fined. This has occasioned a very brisk business in car washes in the environs of the city (The Toyota was washed 3 times in the 6 days I was there.) Out of the 5 provinces, cars registered in 2 (Dashoguz and Mary) cannot enter Ashgabat, whatever their colour and state of cleanliness – they must be left on the outskirts. The city roads are in perfect condition, wide and spotlessly clean. Very few people outside, except for the street cleaners (mainly women with brooms). No traffic jams. There is a sterile and sterilised feel to the town, as after an apocalypse. However, when the night falls, the psychedelic multicoloured lights play on every building, including the high rise apartment blocks.

The monuments are highly visible, grand and quite literal: the monument to Independence is 91 metres tall as the event happened in 1991; the monument to Neutrality is 95 metres tall (1995). Every roundabout has a monument as a centrepiece.

There are some odd things – such as the largest (and only) Ferris wheel inside a building (I did ask, why?). The national flag pole may not be the tallest but is the only one in the world with a jet engine installed to ensure steady fluttering. The five tribes that make up Turkmenistan are represented on the flag with the ancient symbols often seen in their carpets; the National Museum of Turkmenistan incorporates the five pillars inside its architecture, the Memorial complex has five pillars to commemorate the loss of life in the war, there is a 5-headed eagle…

The visit to Nokhur village (where people put ram’s horns on the graves – one story is that it’s to ward off evil spirits, the other that it is just a decoration) finally gave me an opportunity to see how ordinary people live.

I enjoyed the visit to the Carpet Museum. We all know of the “Bokhara” carpets as the best quality hand-knotted ones. But they were only SOLD in Bokhara and have always been made by the Turkmen people. I did drool over a couple of them. Later I really wanted to buy one (in the shop in Mary) – but I would not have been given an export license as it was over 60 years old.

Turkmen are well known for their horsemanship and I was looking forward to seeing the “golden horses”. The Stables near the race course is a home to 600 horses, the Akhal-Teke among them. (I was told that the late Queen was gifted an Akhal-Teke horse by Turkmenistan and the grooms were convinced that the horse had been painted gold and tried to wash it off.) I could have had a ride ($10). Were I a better horsewoman, I might have had a go. They all looked well looked after, if a little frisky (the black stallion is known for being headstrong).

The original programme had me staying in Ashgabat for 3 days, with a couple of trips out. As we more than covered Ashgabat in 2 days, we headed to Mary – the old Merw of the Silk Road (the new town is some 45 km southwest from the ancient city – the river Murgab changed course. Merw is 350 km away from Ashgabat on the road that could be better. There are a number of checkpoints where everyone must slow down; there are also random stops and car document checks along the road. Having the green license plates (a government vehicle) helps but is not a guarantee. (The foreign business partners/investors have yellow plates; the diplomats have blue; folk have white.) One is not allowed to take photos of the checkpoint or police in action. It was good to get to Mary a day early – poor Guwanch would otherwise have had to drive some 800km in one day on those awful roads. It also gave us a nice evening out – dinner and disco!

The ancient Merw did not disappoint. It used to cover some 1000 hectares and was the largest city in the world at its peak – 1/2 million people lived there. The conquerors and emperors came and took and destroyed and rebuilt. The far stretching walls, some fortresses and Ice houses still stand. And the camels graze where the merchants traded and the caravanserais stood.