Took a taxi from Samarkand, Uzbekistan to the Tajikistan border – an easy, straightforward crossing. Panjakent, Tajikistan, is a provincial town that would be no different to any other, were it not for two important archeological sites: the ancient Panjakent that was a flourishing Sogdian town (by now, the names of various khanates, emirates, empires and kingdoms do roll off the tongue) in V-VIII centuries (until the Arab invasion); and Sarezm, which “dates back to the 4th millennium BC and is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site“. Ancient Panjakent was abandoned suddenly (in the face of fierce attacks) and never rebuilt – some therefore call it the Pompeii of Central Asia. (Most of the best preserved and important items have been taken to the Hermitage by the Soviet archeologists who worked the site in the 60’s andd70s. A few items are in the Dushanbe National Museum.) I climbed the two hills old Panjakent was built on and even my imagination had difficulty seeing it in its heyday. Sarezm is “of great interest for archaeologists as it constitutes the first proto-historical agricultural society in this region of Central Asia” (Wiki).

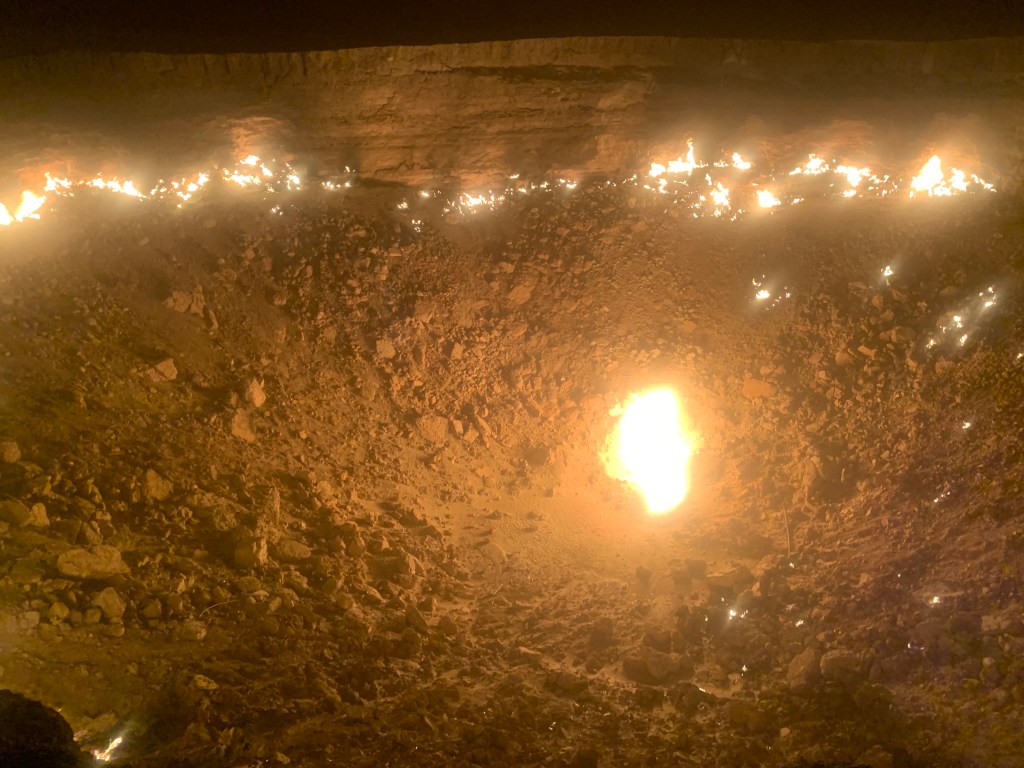

But the trip to the Seven Lakes (HAFT KUL in Tajik) in the foothills of the Pamir range was terrific (and terrifying): Rohim, the taxi driver, owns a Mercedes automatic (with summer tyres) just fine for dry, asphalt roads. The road to the lakes is a narrow, rough, unpaved snake, strewn with stones fallen from the sheer mountain sides, riddled with potholes and having bite-shaped chinks missing on the steep slope to the lake side. There was also snow, and on one hairpin bend Rohim had five goes before making it over the icy bit. The road goes along the canyon of the river Shing. There is a gold mine and an ore processing plant a third of the way up – there was a lot of dust on the way – and silt and waste from the processing go into the river. Higher up though, the water is pristinely clean. (We took with us a dozen or so plastic gallon containers to bring back fresh water from the top lake for Hajji, my host.)

The first lake is called Eyelash, because of its shape; the second is Soja – Shady; the third is Gusher – Nimble; the forth is Nofin – belly button; the fifth is Churdak – Small; the sixth is Marguzor – Blossoming Place; the seventh is Hazorchasma – a 1000 springs.

Life in the mountains has a different, much slower pace. Yes, there are satellite dishes and mobile phones, but laundry is still done by the lake, the most reliable transport is by donkey, and visitors are still interesting enough for the children to gather and watch.

I took the shared taxi to Dushanbe – a little more expensive than the marshrutka minibus but much more comfortable. Hajji, the owner of the hotel where I stayed, organised for the taxi to pick me up at the hotel and Hajji made sure I got the front seat, so no squeezing in the back (and it was a squeeze: 3 people and a baby.) It is a 3,5 hour journey on a good road through spectacular mountain and canyon scenery along the Zarafshan river.

Dushanbe is a young capital. There is little to see from before the beginning of the 1930’s – the town is all Soviet central planning snd building – and nowadays they are getting rid of some of the heavy Soviet constructions. There are many parks, squares and fountains (though all water features were wrapped up against the frost). And plenty of sculptures and monuments: every town has the statue of Ismaili Somoni, the 10th century emir, seen as the father of the Tajik nation; and the poet Rudaki is honoured in statue and park and street names.

The electronic display outside the Ayni Opera House advertised Tchaikovsky’s Idomeneo among other things and I thought, yippee! The lady in the booking office was very sorry, but the opera had been cancelled (no reason given). But I could go and see a musical drama for children the next morning… so I did. The Rabbit with His Nose in the Air (in Russian) was a (cautionary?) tale of the downtrodden and frightened animals who manage to outwit the ruler Lion (who wants to eat one of them). Thought there may have been a subtle lesson in it to teach the children how to get rid of dictators… The music ranged from Enio Moricone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly to the Sugar Plum Fairy. The theatre is a nice neoclassical building from the 1940s. Not far from the Ayni Opera House is the National Museum of Antiquities where the pride of place goes to the Sleeping Buddha, at 16m the largest statue of him in the world (since the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001). Lots of other interesting exhibits, but not many of them have an explanation in English (and even Russian was scant). I found the polystyrene pieces holding parts of antiquities up odd – as if temporary has become permanent.

Left Dushanbe in the rain to fly to Khujand (near the Uzbekistan border, as I needed to dip into Uzbekistan to get to Kyrgyzstan – the land border crossings between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are not open to foreigners as yet). Khujand welcomed us with snow – though the locals kept saying “it never snows here”… The bazaar is, as always, a place of colour and movement, hawking and fascination.

Arbob Cultural palace is a wonderful oxymoron: built in the early 1950s, to be used by the workers of the kolkhoz/sovhoz as a place for meetings and entertainment, it is based on the tsarist Winter Palace in St Petersburg. The driving force behind the construction was a local Tajik, Urukhoajev, the leader of the collective farm and a member of the Soviet leadership in the area (it seems even Stalin respected him – when the order had been given that everyone had to wear a military uniform to Soviet meetings, Urukhoajev was permitted to wear the traditional Tajik clothes). The palace has been built with local labour and local artisans did all the decorating – from woodcarving to painting intricate designs on ceiling panels, to stone and plasterwork statuary. It is now a museum, but also used for special state occasions – and for wedding photos.

I spent a day in Margilan, Fergana Valley, THE silk town in Uzbekistan. The town is synonymous with silk production – the Yodgorlik silk factory still uses traditional hand-weaving method for some of its products, and it is fascinating to watch the women work (women weave, men dye the silk thread). The Institute for the Research of Natural Fibres showed me around too – they investigate and test which mulberry trees (and there are quite a few varieties) produce the best leaves-food for the silkworm, and through selection and feeding of worms work out which produce the best and longest thread – some cocoons will have more than 2000m of silk thread.

Getting the ticket for the train from Margilan to Andijan (a 45 min journey), close to the Kyrgyzstan border, was a lesson in patience. I inadvertently got to the ticket office at 13:40, so it was closed for lunch (a lot of public service places close for lunch between 13:00-14:00 in these parts). Went and had a cup of tea and got there soon after 14:00. The queue (a loose term) seemed long and it was a nice day, so I went for a walk. By 14:30 the queue had not changed much (still the same 5 people) but I thought I’d give it a go. By 15:00 I could ask for a ticket, only to be told that it was a local train, leaving at 07:00 and to come buy the ticket in the morning before I got on… Managed to persuade him that he could issue me a ticket as I was there.